Here's a photo of our 4-year-old daughter Elise surrounded by Cholla cacti in the desert.

A stunning desert sunset...

The week in Southern California followed and we stayed with relatives in sunny Orange County – famous for the beach, but not a rock-climbing Mecca. Regardless, we managed to sneak out for a long and exhausting day to visit the world famous crags of Joshua Tree, about two hours distant. I’m a sport climber and have spent most of my climbing career combing the planet for spectacular overhanging climbing (personal recommendations: Red River Gorge, Gorge du Tarn, Teradettes, Rodellar, Kalymnos), but since I learned to climb in Squamish and have resided there for over 15 years, I’ve done my share of crack climbing. Like most sport climbers, the wider sizes of crack feel horribly difficult and awkward to me, but thin finger cracks allow me to exercise some of my granite-honed face climbing skills and can, at times, provide a great way to branch out into another area of climbing I’m not as familiar with. Knowing I’d only have a single day at J-Tree, my goal thus became clear: the finger-crack splitter, Equinox.

Southern California at Christmas: sunset over Catalina island.

Simon Carter's photo of Figures on a Landscape at J-Tree, courtesy of Climbing.com.

Simon Carter's photo of Figures on a Landscape at J-Tree, courtesy of Climbing.com.

Equinox (5.12c) is a time-honoured classic that sits in a remote corner of the park. As far as I know, it was first TR’d by John Bachar, first redointed by Tony Yaniro and first on-sighted by Jerry Moffat, a serious trio of hard-hitting and influential climbers. The difficulty is moderate by today’s standards, but Joshua Tree ratings are stiff and I was told the quality was second to none. The laser-cut finger crack splits a smooth, slabby dome that is perched majestically on top of a jumble of large boulders – it’s impossible to miss. Research amongst my guiding friends helped me prepare. I was advised on rope length (60 m Mammut Infinity), shoes (high performance edging/smearing) and rack (triples of blue, yellow and orange TCUs as well as singles of the next two sizes). I was also advised about the approach, which involves a 30-minute hike across the desert to an indistinct mound of granite that offers few clues as to the correct destination.

Beautiful desert light...

Our pre-arranged day dawned cloudy and cool, but the forecasted winds were calm which, I’ve been told, is of paramount importance in J-Tree. A quick stop at the visitor’s centre confirmed driving directions; we found the parking area without incident. The approach went well, with a few minor corrections, but the scramble through the boulders to the base of the crack was trickier than expected (stay left), especially with a 4-year-old child on your back! With only one short day to try a classic route, it’s easy to get nervous and I started feeling the pressure to perform. A couple of friends had told me I should try to flash it, but my 40-year-old analytical brain told me that approach might be risky. I knew I’d be very anxious, would put in way too much gear, getting pumped in the process, and likely fall with major gobies preventing a solid redpoint burn for my second try. Also, with no decent warm-ups for miles, I’d be going up cold (literally), further reducing my chances. As it turned out, my intuition was dead on…

A foreshortened view of the crack in poor light.

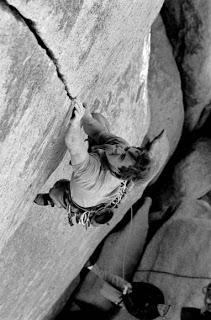

The cloudy December day was brisk, and when I started up the crack, I felt wooden in my movements. A quick slip found me hanging on the rope and working out some moves, which helped me loosen up, both physically and mentally. Quickly summed up, the climb goes as follows: An 80-degree wall, with awkward, thin-finger locks and laybacks, rears into a gently overhanging sheet of smooth, desert granite, where the locks get solid, but the footholds on the face all but disappear. This is the crux. Powerful pulls with sketchy feet gain sinker finger locks that eventually lead leftward to some thank-God foot chips that allow weight to go back onto your legs. The difficulties slowly ease, but the route remains tricky to the end. My work session didn’t go as well as I’d hoped and I found myself having a hard time remembering what to do – the crack was very unwavering in its appearance. Since time (and skin) was limited, I lowered off, rested and prepared for what would likely be my only redpoint attempt.

This photo is by Warren Hugues and shows a climber at the crux locks.

The wind picked up and the day grew colder. Since it was impossible to run around in the boulder-jumbled landscape to warm up, I decided less rest was prudent. Standing at the base shaking in the gusty wind, I looked up at the crack with trepidation. I pulled onto the wall and started up the techy opening moves. My foot skated off a grim smear about 10 feet off the ground which, although I didn’t fall, caused me to tense up more than I should have. At the steep crux above, I pulled with all my might and managed to sink the first positive lock above, thus opening the path to the summit. The problem was, I tore half the skin off my middle finger in the process and spotted the damage in my peripheral vision as I forged upward – a disconcerting image for sure! Knowing full well I’d not have another chance now, I went into battle mode, always a mistake halfway up a sustained, pumpy climb. I gripped the positive locks like they were smeared with grease, pumping my forearms to the max. I stopped breathing and my vision narrowed, barely allowing me to remember my “sequence” or see the desperately minimal footholds I’d so carefully tried to imprint on my memory. I almost fell off and each move started feeling utterly desperate. I’m sure the knowledge that you’ll never likely return to a classic route can provide an inner strength normally unreachable on more accessible climbs. For me, this knowledge pulled a battle-instinct from my core and I put 110% into the final 20 feet of climbing. Miraculously, I found myself holding the top of the wall with a claw-like grip that wouldn’t relax. Ten minutes worth of composure in the buffeting wind allowed the final moves to the anchor to pass uneventfully. And just like that, the ascent was in the bag.

Those gobies are going to hurt in the shower!

Days later, the wounds in my fingers were still weeping, but we still managed to check out another local climbing spot – Riverside Quarry – between visits with the relatives. This crag is probably the most un-aesthetic cliff I’ve ever climbed at, but the 30-40 m long routes up comfortized edges and jugs were the perfect antidote to the Joshua Tree skin-shredding that occurred days before. The cliff climbed like a turbo outdoor climbing gym with closely packed routes and a great spread of grades. The routes and images of this cliff will likely quickly fade, but the memories of that day in the desert at Joshua Tree will endure, I’m sure.

The quarry...

Relaxing at a So-cal beach with our daughter.

Happy holidays to all!

Marc Bourdon – Squamish, BC

2 comments:

viagra online

buy viagra

generic viagra

This is a very wicked guide mate. thanks for sharing!

Post a Comment